By Jane Berg and Tamara Enz June 6, 2025 What is the Internet of Animals? For…

NASA’s Student Airborne Research Program: A unique NASA internship

In this episode Dr. Emily Schaller talks about running SARP, a unique NASA internship that gives undergraduate students hands-on experience in atmospheric science research.

Listen here or on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Soundcloud, Spotify, or Google Podcasts.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Meet Emily Schaller

So hi, I’m Emily Schaller, I’m the science and communications program manager for the National Suborbital Research Center here at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute. Quite the long title, I guess.

Dr. Emily Schaller

My role is running the NASA Student Airborne Research Program, or SARP, which is a summer internship for undergraduates who are in between their junior and senior year majoring in any of the STEM disciplines: science, technology, engineering and math. They come from schools all over the United States and we bring them out to California, usually, when there’s not a pandemic, and they get to fly on board a NASA research aircraft and do Earth system science from onboard the airplane.

And then in addition to SARP, I also help coordinate — again, not in pandemic years — education and outreach in the field for airborne science program missions all over the world. In that role I’ve gotten to literally travel to the North Pole and the South Pole and everywhere in between, reaching out to students and teachers and the public. Whenever we have an airborne science campaign that is based in a foreign country or in the United States, I’ll help coordinate tours of the aircraft for the public or visits to local schools or things like that.

I’m an astronomer by training, I have a Ph.D. in planetary astronomy, but throughout my PhD and in my postdoc years, my heart was always in education and outreach. Whenever there was an opportunity to go talk to a school or do any kind of outreach event, that was what I always loved the most. I happened upon this job with NASA by literally looking at an AGU Eos — they used to print it out and mail it, and it had a job register in it. And I wasn’t even really looking for a job at that point because I still had another year left of my postdoc. And this job with NSRC wanted someone with a PhD who could run an internship program, and I just jumped at the chance because I was so influenced by an internship program that I did when I was an undergraduate at Ames. So I left my postdoc and have been working for NSRC ever since.

How SARP came to be

So SARP was started in 2009 with the goal of addressing some educational objectives that had been laid out by NASA, specifically involving students in Earth science research. One of the things that we find among the general public and also students is that a lot of people aren’t aware that NASA does earth science. So, you know, you hear NASA and you think space and astronomy and things like that. And of course, NASA does all those things. But Earth science is a huge part of what NASA does. And so exposing undergraduates to NASA research and the earth sciences early in their careers, our hope was to show these students that the skills that they have now in whatever they’re majoring in, whether that’s math or physics or chemistry or biology, they can apply that background in those skills to the study of the earth system. And so the goal was to get more students to be aware of this really cool job opportunity with NASA studying the earth.

SARP students at work

We definitely have a lot of students who come in as a straight physics major, for example. As grad students, I often will then see them participating in airborne science missions. So it’s really fun. Now we have so many alumni that there are almost no missions now where there aren’t some SARP alumni participating. It’s unusual to to not have any kind of SARP connection, whether it’s students, mentors or faculty. One of our alumni is actually the co-PI of the Tracer-AQ Air Quality Mission that’s taking place. It’s going to be one of the first missions coming back and studying air quality in the Houston area, and, you know, she was a student in SARP in 2012, and then she came back as a mentor, a graduate student mentor, and then she came back as an instrument scientist, and now here she is running this airborne campaign. So it’s really awesome to see that evolution because I knew her when she was an undergrad.

I feel very sort of maternal toward the students, you know, and just getting to track them and see what they’re all doing and then, you know, when they send me emails like, oh Emily, I just got this job or I just got my Ph.D., it’s just a really wonderful part of my job to see that.

SARP Week 1: Learning about airborne science @ NASA Armstrong

So it really varies a lot by week. So the first week of SARP, we bring all the students to NASA Armstrong down in Southern California in the Palmdale location. And that first week is kind of background. They get a lot of lectures from lots of different folks in the field. So they they learn about NASA, Earth science, atmospheric chemistry. They learn about the different instruments they’re going to be using. They get tours of the facility. They get to walk around and see the planes, learn about what the different aircraft do. Often they’ll meet with pilots and just kind of get an overview, a feel for what we do in airborne science at NASA that first week.

SARP Week 2: Flight week

And then the second week is the flight week. And that’s the kind of exciting part because every student gets to fly onboard — it’s usually the NASA DC-8, but we’ve used some other aircraft depending on the year, and they get to fly on board the aircraft, assist in the operation of various instruments onboard the aircraft. That’s really what bonds the group.

Flight week at SARP

So airborne science flights are often not very similar to your typical airline flight. The goal with a typical airline flight is get your people from one location to another, straight and level flying. That’s not the goal in an airborne science mission. Oftentimes we want to take samples of the atmosphere at various heights in the atmosphere so we might be doing a spiral or we might be flying very low to the ground to sniff a source of some kind. And so it can be very, very bumpy. And typically about a fourth of the students will lose their lunch in the process.

This is actually a great bonding experience. In 2019 students actually made a t-shirt that said ‘I puked’ or ‘I didn’t’, like ‘I had a NASA airport experience.’ And they had the list of people who puked and the list of people who didn’t. And that’s what happens on these airborne missions. Even very seasoned folks who’ve been flying for for many years as NASA scientists, that sometimes happens.

So that bonds the group. They get to acquire their own data, which is really fun, and then they go out into the field. So they all get a field trip and they all get to fly on the plane. So that’s the second week and that’s all takes place in Palmdale.

SARP Weeks 3–8: Research groups at work @ UC Irvine

And then we bring them all down to the University of California, Irvine, which is where the program has been based since its inception. The students, live in dormitory housing there. Each day they they meet with their research group mentor and frequently with their faculty members as well. Not all the faculty are based there, so there’s a lot of Zoom calls that happen, even in pre pandemic times. But the faculty are able to come down and meet with the students to help them craft their individual research projects that each student develops.

So in the the six weeks that we’re down in Irvine, we expect the students will work approximately eight hours a day on their research projects. But we give them a lot of freedom in how they structure that. We treat them like graduate students — there’s a lot of flexibility. But we also throughout that six weeks, we provide a lot of enrichment lectures. So I bring in scientists from the local area. And that was actually a lesson learned from the pandemic, is that we don’t need to be limited by scientists who are just in Southern California. So during the pandemic, we had lectures from folks all over the country. We even had an astronaut lecture to us.

Then we get to the last week and the students are each working on crafting their individual research project. And so they all have to submit an abstract, an AGU-style abstract, as well as deliver a 12 minute oral presentation. And so the last week the students are preparing for that. They give their final presentations, we record them. And a lot of those presentations, I think, are really useful for the students, because oftentimes when students are applying to graduate school or applying to jobs, they have a professional presentation that they’ve given and they can point to that.

And then at the conclusion, we will typically fund four students to then present their research at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco. Oftentimes more are able to go and present their research, students can get funding from other sources or things like that. And then we start all over again with the next class.

SARP during the pandemic

A SARP student receives their box of air canisters

For virtual SARP I was completely thrown for a loop, but we did manage to have the students still have hands-on research. So what we did was we mailed evacuated air canisters out to the students so that they could take air samples of their local environment, which is really interesting, right, because of the pandemic and the decreased emissions all over the country. We wanted to try and track that. And so once we realized in late March of last year that the pandemic was going to make it so that SARP was not going to be able to happen, Rowland-Blake Lab just jumped into gear and prepared these huge boxes of canisters, sixty-five pound boxes that they sent out to each student, and then students went out — whether they could go in their backyard or some of them were able to go a little bit farther to a park or something like that — to take kind of a background sample of their local environment starting in April to the end of the summer. And we’re doing it again this year so that we can then have a comparison. Some of the students are in similar locations, in the same cities, but obviously they’re not all in the same locations. But we’ll be able to have a nice kind of background understanding of missions of different gases during the pandemic. I think it’ll be a really great scientific data set that will be mined by students and also others for years to come.

SARP student collecting air samples

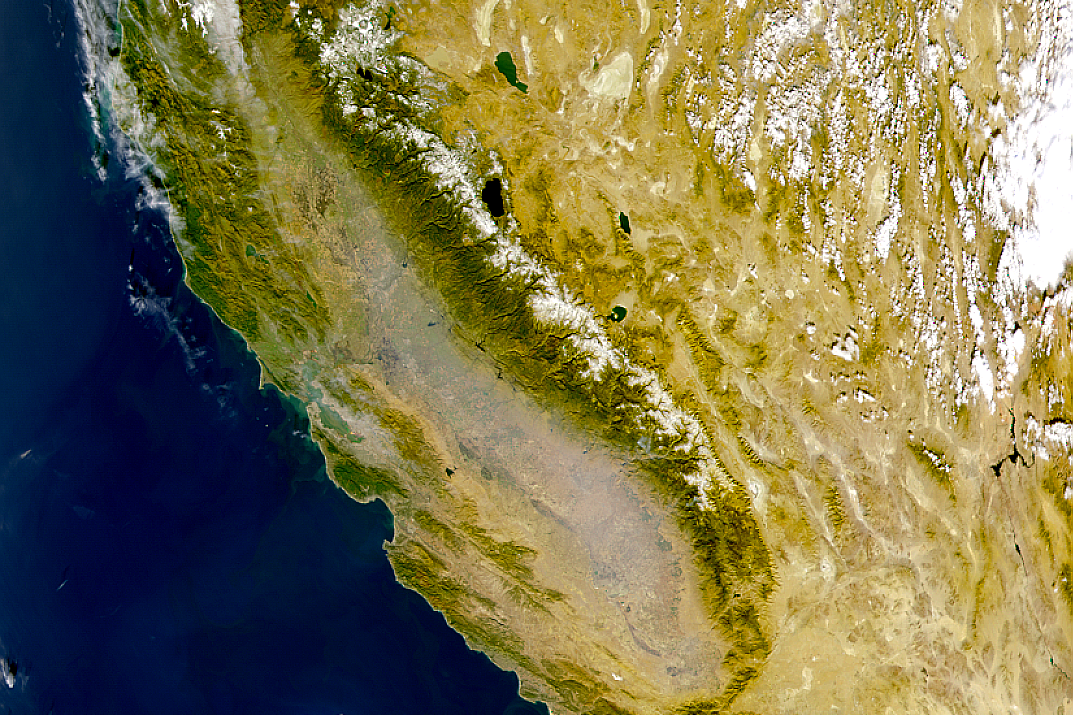

And so the students, while they collected those air samples, they still did individual research projects from previous year’s data. And it’s really lucky that the program has been going on for so long because we do have this long term data set of airborne observations, ground observations over southern and central California. And so students were able to use that data set as well as NASA satellite data. And so we allowed students to kind of go broad with where they wanted to do projects this summer and not restricting them really geographically at all, which — we we never restricted them fully, but we always encouraged projects in Southern California using the data from SARP. But since we didn’t have that data this past summer, we had some really great projects using data from all over the world.

SARP mentors and faculty

The faculty members are so important to SARP. They are essentially donating their time in order to work with these students, and they are really the heart of the program. We could not do it without our dedicated faculty members. We have one who’s been with us from the very beginning, Don Blake, and that was initially why we based the program in Irvine, because his lab, the Roland Blake lab, is there. Raphe Kudela has also been with the program since the second year of the program. He leads the Ocean Science Research Group. And then we’ve had an assortment of other faculty members who’ve stayed with us anywhere from two to five or six years. And we’ve just been so lucky with how dedicated all the faculty members have been to SARP.

And oftentimes one of their graduate students will be who we call the mentor, the graduate mentor. And so typically it’s an upper level graduate student of one of the faculty members, or sometimes the graduate student can come from a different lab or research group. And the research mentor actually lives with the students. They’re literally living with and working with the students all day, every day. And so it’s a very challenging role for the graduate student, but it’s a really great role for the graduate student because it enables them to essentially kind of run their own research group and get the experience of being a faculty member or P.I. early on in their career. And some of them find they really love that and some of them find that they don’t. And so I think it’s a really great experience, a really unique experience for a graduate student to get to have that kind of ability to to manage people so early on in their career. And many of our graduate student mentors have gone on to great things as well. The deputy director of the Airborne Science Program was a SARP mentor originally. And so it’s really great to to see what all of the students and mentors do.

The impact of airborne science education and outreach

I think it’s so important for there to be educational components on all of these airborne science program missions. For example, actually, there is a podcast that a student from SARP 2020 just did. She was stationed in the Air Force in 2016 out in South Korea. And we did an outreach event there for service members. We were stationed there for an air quality mission, studying the air quality in South Korea. And so I was out there coordinating education and outreach and was going into schools, giving talks on the air base to the children of service members on base. But we also did some outreach. Like, ‘come see our plane and walk through’ to anybody on base who was interested. And it turned out that Katie saw our plane and came and chatted with me about Earth science and this conversation and this experience, learning about the fact that NASA does Earth Science, convinced her to go back to school. And then she got her undergraduate degree and then she applied to SARP. And so it really came full circle for me.

SARP students at NASA Armstrong

She actually was just interviewed by her school and I was listening to her podcast and actually teared up just because, you know, to know that that one outreach event that we did had such a ripple effect down the line on her life was just, I mean, just amazing, the effect that — and you never know, right? There could have been other people that we don’t know of that had a similar story. So I love that with with outreach, just down the line, the impacts that you can have, you never even know. Or if you talked to a group of third graders, there might be some in there that are really motivated and that convinces them to go into science. You never know.