Our story

How our founder Robert Bergstrom’s decades-long quest to make an impact on environmental research and regulation led to where we are today.

On April 22nd, 1970, Robert Bergstrom was at a Purdue University party to celebrate the first Earth Day. He was about to wrap up a Master’s degree in mechanical engineering and stood chatting with his thesis advisor who knew he didn’t have a Ph.D. topic yet. “Well,” his advisor said to him, “if you’re interested in the environment, I have an idea for a study.” He showed Bergstrom a recent article about particles coming from air pollution, stating that maybe they were decreasing solar radiation and could be causing the cooling trend of the prior years. Bergstrom thought “We can do better than that,” and he started to build computer models predicting the radiative properties of atmospheric particles.

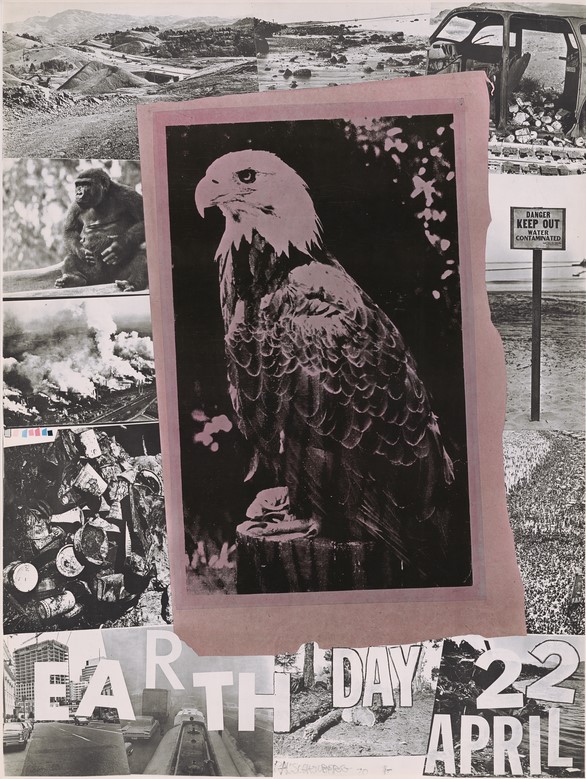

Poster by artist Robert Rauschenberg in honor of the first Earth Day, 1970. Image: National Archives, Records of the United States Information Agency.

On his advisor’s suggestion, Bergstrom sent in a proposal to the brand-new Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to fund his thesis work. He was awarded funding and by graduation had published three papers about the effects of aerosols on climate.

From Purdue, he went on to do postdoc work, first in Mainz, Germany, and then at NASA Ames Research Center, before taking a job with an environmental consulting group in San Rafael, California. It was through this work that Bergstrom became interested in environmental litigation and did a few stints as an expert witness. He saw an opportunity to do more—most attorneys didn’t know anything about the science involved in their cases, but Bergstrom certainly did. He was admitted to Stanford Law School and stepped into a new career. “My whole life changed,” said Bergstrom, “but you can‘t pass up an opportunity to go to Stanford Law School. I would have spent the rest of my life thinking ‘I should have done that.’”

At Stanford, Bergstrom set out to focus on environmental law, but there were only a few environmental-law classes available. He joined the California Bar in 1983, and he worked as an environmental lawyer at a large San Francisco firm for a year before signing on as a litigator for the EPA Region 9 in the Pacific Southwest region.

The mining town of Morenci, Arizona, half hidden by smoke from copper smelter stacks, 1972. Image: National Archives, Environmental Protection Agency.

Bergstrom spent nearly a decade with the EPA. In addition to developing enforcement actions against copper smelters in Arizona, he helped streamline the bureaucratic system to make it easier for the EPA to bring cases to court. He received the EPA Gold Medal for Meritorious Service in 1991.

In 1992, Bergstrom decided it was time to return to his roots as a research scientist and continue his work on air pollution and its effects on climate. He reconnected with his former colleagues at NASA Ames and applied for and received funding to “quantify the effects of soot on increased solar radiation in the atmosphere and its consequent contributions to climate change.” Bergstrom’s wife Sharon Sittloh suggested he start a nonprofit to facilitate the funding of his research. He liked the idea and had the right mix of experience to do it: while working as a lawyer, Bergstrom had also co-founded a software company called Legisoft, which produced a best-selling software application called WillMaker (now an Intuit product). In 1993, the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute (BAERI) was born.

In the beginning, BAERI was an organization of two—Bergstrom and Sittloh—founded to enable the research of a single environmental researcher. With Bergstrom’s success, colleagues began to take notice of BAERI, and they asked him to replicate BAERI’s model for their postdocs’ research. Bergstrom’s first response was “...No, no, that isn’t for me.” They were persistent, and BAERI began to grow, with Sittloh as Executive Director for the first 10 years.

From the moment they had five employees, big enough to qualify for group health insurance, Bergstrom set up the best benefits he could find, hired someone to do accounting, ran everyone’s payroll, and treated the researchers the way he wanted to be treated himself. (“Which means,” he said with a laugh, “you leave people alone unless they have problems and they ask for help.”)

BAERI continued to grow entirely by word of mouth. In 2012, Bergstrom was named the Principal Investigator for the NASA Ames Research Center Cooperative Research in Earth Science and Technology (ARC-CREST), a 10-year, $137 million cooperative agreement with four collaborating institutions: BAERI; California State University, Monterey Bay; University of North Dakota; and University of California, Davis.

Today, 30 years after its founding, the Institute employs over 150 researchers in the Earth and space sciences. Though the budget, scope, and complexity of the organization have changed over time, BAERI’s fundamental purpose remains the same—to be an organization built by researchers, for researchers, that enables groundbreaking research.

Dr. Robert Bergstrom, Founder of BAERI. Image: Gailynne Bouret, BAERI