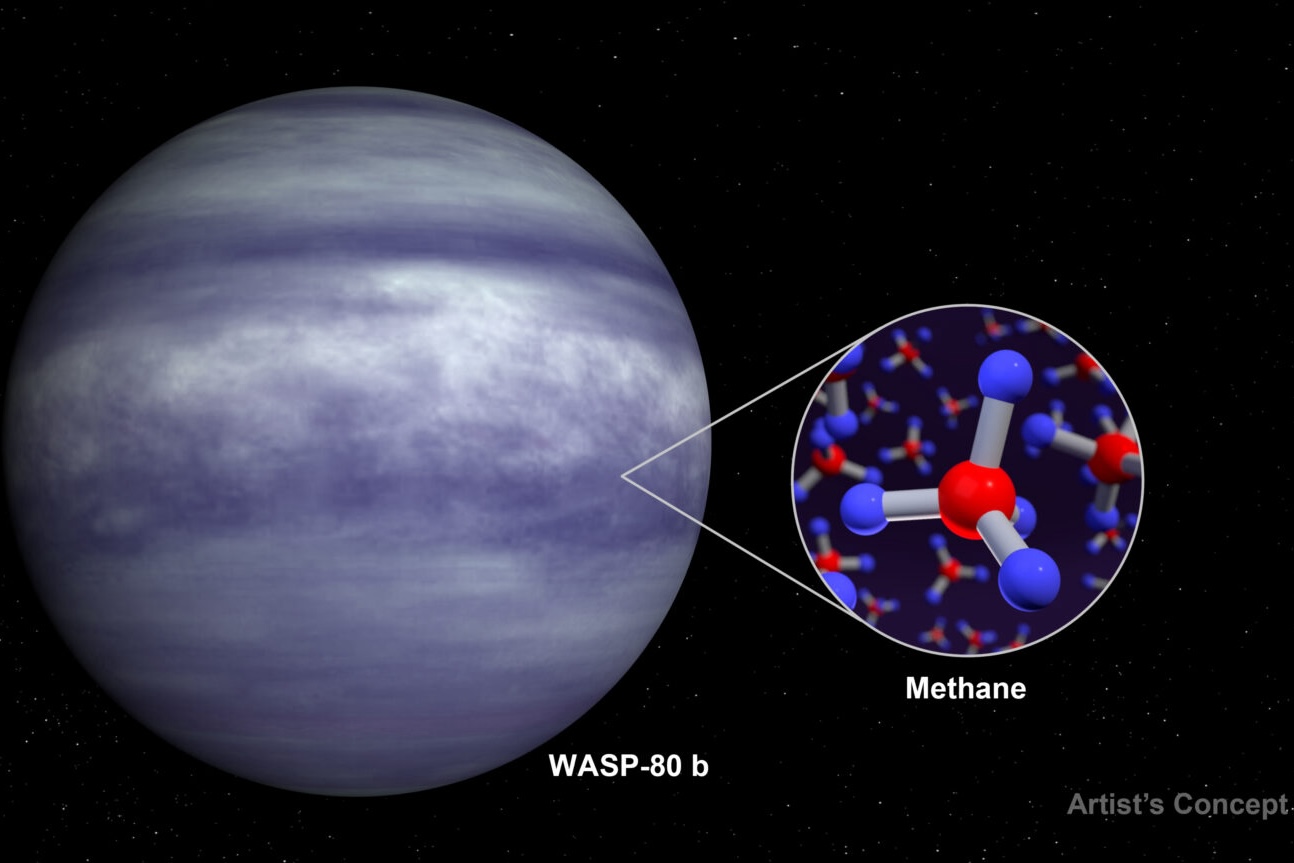

BAERI’s Taylor Bell and a team of researchers have identified the presence of methane in the atmosphere…

Exoplanets! — Part 2

This two-part series is all about exoplanets, planets outside of our solar system, and how they and the stars they orbit are a key part of the search for extraterrestrial life.

In this episode, Part 2, we talk with two BAERI folks, astronomer Geert Barentsen and science communicator Kassie Perlongo, about their citizen science accelerator, Planet Hunters Coffee Chat, where they teach you how to dig into space telescope data to look for planets, and other potentially weird things, yourself.

Listen here or on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Soundcloud, Spotify, or Google Podcasts.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

BAERI: This is For the Love of Science, a podcast from the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute.

I’m Erin Bregman. In this show, we hear directly from the institute’s scientists, engineers, and mission specialists about the groundbreaking research they’re doing right now in earth, environmental, and space sciences, and learn about what their work can teach us about our earth and our universe.

Welcome to part two of our two-part series on exoplanets. If you missed Part 1, I highly recommend you check it out. In that episode I speak with Christina Hedges and Ann Marie Cody about their work on exoplanets, weirdly behaving stars, and how it connects to the search for alien superstructures, among other things.

In this episode, Part 2, I talk with two more BAERI folks, astronomer Geert Barentsen and science communicator Kassie Perlongo, about the citizen science accelerator Planet Hunters Coffee Chat, where they teach you how to dig into space telescope data to look for planets, and other potentially weird things, yourself. To start us off, here’s Kassie:

KASSIE: My name is Kassie Perlongo, and I’m a science communicator and a science writer, and I work for the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute. But my primary job is working with the Science Directorate at the Ames Research Center.

GEERT: Hi, my name is Geert Barentsen, and I am an astronomer, also at the Bay Area Environmental Research. And my day to day job is mostly using data from NASA’s Kepler and TESS space telescopes to make all sorts of discoveries and analyses to help us better understand the universe.

Image: NASA-JPL/Caltech

I think if we want NASA’s mission to succeed, then it’s important to explain to the public what we do day to day for two reasons. A, because we live by the grace of the public, the public funds NASA to make discoveries. And secondly, if we’re going to make big announcements about discoveries we’ve made, if we don’t also explain how we make those discoveries, then the public might not even believe us. One of NASA science’s biggest goals is to search for extraterrestrial life, like, are we alone in this universe or could there be other life forms out there? That’s a big question. And if we ever want to claim that we found aliens, then we better have some really good evidence and we better take some effort to take society along for the ride to explain how we came to these conclusions because at face value, people might be very skeptical, rightly, about such a claim.

KASSIE: There’s already a citizen science project in existence with TESS, and that’s on the Zooniverse platform, and it’s called Planet Hunters TESS. But we were thinking of it as: how do we take this to its next level? Citizen science work is typically… you have a project, an idea, a research project or an idea, and people will either submit data or help to classify data for that particular project. And we’re basically, as Planet Hunters coffee chat saying: All right, you’ve already got this amazing platform, Planet Hunters TESS. You’re doing citizen science work. But have you thought about maybe expanding your knowledge? Do you want to actually work with some of the resources and data that astronomers are already using? Do you want to learn how to do some coding?

And so we’re helping them by providing these videos. That’s myself and Nora currently, but we’re going to try to see if we can do other guest hosts and hosts as this project expands. And then also these live office hours, which I think is really the jewel in the crown, so to speak, because citizen scientist then have the opportunity, much like when you would go to a lecture at university and you’re like, OK, that lecture was great, but I need help breaking down the fundamentals. And so you would go to these office hours with your TAs and with other companions. So this live office hours is: Hey, you get a chance to speak to astronomers or astrophysicists, whoever is working with this sort of data. And you can just ask questions about it and you can talk to them like you’re talking to a peer. We want to accelerate people’s knowledge within this area. So we’re piggybacking currently on a project and we’re going to try to expand it a little bit more.

This was a collaborative process. It was myself and Geert and Jessie Dotson initially sitting down and having this conversation, and then we were able to talk to Nora Eisner, who’s part of Planet Hunters TESS. So she is the project lead, and it sort of morphed from there. So it just became this interesting way of doing citizen science work. And we call it Citizen Science 3.0.

It’s not just, you’re classifying data and then you’re done and dusted. You can attend our live office hours. You can give us direct feedback. What kind of episodes do you want us to film? And so we’re trying to establish and create and curate this two way communication, which oftentimes I think might be overlooked with Citizen Science projects because they’re looking at just classifying certain things and data. And then that’s it. It makes sense for that. But because we’re doing something different, we’re trying to have more involvement within our community.

Image: NASA-JPL/Caltech

GEERT: Doing better at broadening who participates in science is very important, perhaps now more than ever, because a lot of people, perhaps rightly, feel alienated from science. And you know, there’s many reasons why people might feel alienated from science. Like, often they see scientists who have to study for years and years to become a scientist, which requires financial means and time and opportunity. And also then when you become a scientist, often we end up using all sorts of expensive acronyms and terminology, which sounds very difficult because we’ve invented stuff just just to make the language a bit more efficient. But it creates barriers which are very meaningful. And yet, a lot of what scientists do day to day isn’t that hard. Like, for example, just speaking from what I do, what I do is I use a video camera in space to look for planets. And the way I do this is that if the brightness of a star dips very briefly, then I know that there might be a planet there because the planet was blocking the light from the star briefly. Like, it’s not that hard. Of course, the devil is in the details because once you start digging and try to find the smallest ever planet, then you have to really understand the data very well, and you can make it very complicated. But at first level, it’s not that hard.

However, a lot of scientists are really only incentivized to explain their conclusions. And that’s and that’s fun, because they’re often amazing discoveries. But a lot of scientists are not incentivized to explain how they found it, how they found the planet, what they actually saw when they discovered the planet and what methods they used. Like, how did they take the data from a video camera to find that planet?

BAERI: I watched your recording of the first office hours that you did, and I was really impressed just by the level of kind of getting into the nitty gritty details that the volunteer scientists were interested in. And I was curious if anything surprised you about that conversation, and or how it informs what you’re covering moving forward.

GEERT: Whenever I get in touch with volunteer or citizen scientists, it never ceases to amaze me how quickly people are able to learn and adopt all the terminology and become volunteers that are almost indistinguishable from a professional scientist. And one of the biggest reasons for that is that in science and certainly in astronomy, there’s so many niche skills, niche data sets. Every telescope is different. Every science project has its own challenges. Even though it might take many years to gain a PhD in physics or something, it doesn’t take more than a few days or a few weeks for somebody who is very open and willing to learn to become an expert on how to find a planet in this specific dataset, or how to use a specific tool to analyze data. Just because science, of course, by by virtue of the many questions it asks and the many different instruments and experiments it needs, has so many specialized knowledge about very specific experiments and data sets, that it turns out that citizen scientists with maybe a week or two of study can become experts on a topic that 99% of professional astronomers don’t know all that much about.

BAERI: What do you see as the difference then, between volunteer and professional astronomers? Is it just a matter of time or a fluency in the language or..?

GEERT: Perhaps there is one key difference, which is that if you’re professionally engaged in science, which often means that you’re at some institution like a university or some research institute or something, that automatically gives you a lot of access to peers. It gives you a lot of access to colleague astronomers, to conferences, the ability to exchange ideas, to ask for help, to ask for advice, to bounce ideas off people. I think one of the most challenging things for a volunteer is how you access that peer knowledge. Because it’s very daunting to just walk into university and knock on a professor’s door. And the professor is probably busy teaching undergrads and doesn’t have a lot of time. And that is exactly what this project is trying to address, which is offering volunteers who are interested to contribute to science an opportunity to go somewhere to directly engage with people who already know a lot about the specific facility or specific science topic.

And in fact, if you talk to some of the people who’ve been doing citizen science for many years, whenever they do surveys or based on their other experience, whenever they ask their volunteers, what do you want most to become more active or what would help you most? It seems like the most common answer is: we want to have the opportunity to directly engage and talk with professional scientists and astronomers, just to be able to bounce ideas off them and get some advice. And so by having these pre-recorded videos on one hand, and office hours on the other hand, we’re trying to create a space that’s kind of like a little coffee break at university.

KASSIE: I want to just briefly say that we got an interesting email from one citizen science participant. And she said that she’d been part of Planet Hunters TESS, helping to classify potential exoplanet candidates for a few years now. And she was really happy to see these new videos that have come out because she was always curious about the data that she was looking at, and she wasn’t quite sure you know, what kind of resources or what kind of things are…you know, what is this? How do I go about this? And so the videos are helping her to, in these large swaths of things out there could just Google exoplanet. There’s so much stuff. So we’re helping to at least limit and saying, Hey, these are some ideas for you to go about and look at it, and then you can expand and look at more things, and we’re just giving them the tools to present that initially. And I like to think that she’s one of many, hopefully, who are being interested in this.

BAERI: And who is who is getting involved, like who are these people and why are they doing it?

GEERT: That’s an excellent question, because one of the most surprising results that the people that run some of these planet hunting citizen science projects found is that it’s very hard to predict who will take an interest in this. Of course, there are some people who studied physics in school and then maybe did some other job, and now they retired, and they want to connect back to their old love that exists. But there’s also people who absolutely didn’t care about astronomy two years ago, and who just stumbled upon it and figured, oh, you know, I’ll give that a try, and are now writing papers. And that’s fun, because if we can open ourselves up to those non-traditional paths to access or become a scientist, then we also open ourselves up to more diverse skills because often these people had a wildly different background than people who just did astronomy as an undergrad and then did graduate studies and were academics. Like by opening ourselves up to people who perhaps were chemists before, or are just really good at making drawings of things or making graphics, which are all skills we need, we end up doing more diverse and more rich science.

Something that’s perhaps obvious, but sometimes overlooked, is that when somebody asks me a question about the details of some space telescope or how to discover a planet and so on, more often than not, I don’t know the answer. And it would be true for many of my colleagues as well. But what’s different is that because of experience and education, I’ve gotten a pretty good understanding of how I can figure out the answer. And that’s something that’s kind of fun. When a citizen scientist asks you a complicated question, my favorite answer is: you know what? I don’t know…but I can help you figure out how I would figure out the answer. And that’s powerful, because a lot of citizen scientists, sometimes perhaps are intimidated because they’re worried about saying something wrong. Or they might be ashamed of not knowing the answer when in fact, we don’t know the answer more than half the times, we just know how to figure it out. And helping to broaden the knowledge of how you find the answers on the details of a space telescope and so on is very fun and powerful. And I think that could help level the field and remove barriers because you’re helping people jump over the barriers themselves.

KASSIE: And so I mentioned before sort of informally, we’re creating this sort of community, this group. But really, it’s just a place for people to feel safe, to actually ask silly questions, to quote unquote, make mistakes or whatever. That’s what we’re trying to cultivate, and we think that’s really important for science.

GEERT: Yeah, I think the process of science often involves failing a lot, but instead of calling them failure, you call them learning opportunities. And you do that 99 times, 99 learning opportunities. And then maybe that 100th time the learning opportunity goes away and it turns into a discovery. And that’s very common in science.

KASSIE: What do we see next? How do we see this going moving forward in the future? Can we help to accelerate other citizen science projects where we’re creating this sort of good feedback loop between helping and enhancing and giving people the tools and resources? Can we expand this so we’re not only working with planet hunters and creating Planet Hunters coffee chat, but can we actually use the similar formula for other NASA missions? Can we work across, like in the Earth sciences, work with some of the cool stuff that they’re doing?

GEERT: I think the future looks very rosy because more and more, whenever NASA is launching new telescopes into space or new satellites that image the Earth, et cetera, all the data that’s taken these days in almost all cases now becomes public right away. So there’s never been as much data publicly available for people to dig through and extract value out of. So it’s exciting. There’s this massive opportunity, and I think NASA is just starting to figure out and learn how we can present the data in a way that becomes really accessible to the public. And so I think we’re at the start of a sort of a revolution where doing the science is taken out of the hands of just senior folks who’ve been doing this for decades into something that students can do and hobbyists can do.

And perhaps if I can dream really big, then I would like to think that in the future, we could even open up the process of deciding which questions or which missions we should be launching in a way that involves the public.

Perhaps one of the hardest things that NASA does is it will get proposals for maybe a few dozen new space telescopes or science missions. And because there’s only so much money, it often has to pick two or three out of 40 amazing proposals. Wouldn’t it be fun if the public was made part of this process? Right now, it’s some very senior experts who are brilliantly smart people, and they have the really, really difficult job of carefully looking at the scientific merits of each of the new mission concepts. But at the end of the day, asking: Should we be prioritizing searching for life in the universe, or should we be prioritizing how the study of how galaxies first formed or how stars form or how planets form, or how Earth’s climate system works, et cetera? You know, that’s a very difficult choice because all those questions are very interesting. But if we can engage the public in helping us understand where the priorities should be, then we’ll start to get more ownership in society over those missions. And perhaps ultimately, we’ll also just get more missions because more people are excited about the questions and start to appreciate how many more questions we could be answering.

BAERI: Thank you to Geert Barentsen and Kassie Perlongo. Our music is by Danny Clay. You can learn more about the search for exoplanets by listening back to our very first episode, How to Discover a New Planet, or jump in and start learning now at the planet hunters citizen science accelerator, at planethunters.coffee.

That’s it for this episode, see you next time.