A team of researchers, including BAERI alumnus Michel Nuevo, analyzed the oldest organics in samples…

How to discover a new planet

In this episode we hear from two researchers who helped make the data from NASA’s Kepler mission accessible to the public, so that anyone in the world, including you, could sit down at your computer and discover a new planet.

Listen here or on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Soundcloud, Spotify, or Google Podcasts.

NASA Kepler spacecraft in a clean room at Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. in Boulder, Colorado; Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ball Aerospace

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

In 2015, BAER Institute researcher Geert Barentsen moved to California to join Kepler, NASA’s first mission dedicated to the discovery of exoplanets. His position was with the Guest Observers Office, with the goal of opening up the mission’s data to the public.

It was a perfect fit for Barentsen, whose earliest involvement in astronomy included his own experience, long before becoming a professional astronomer, of looking at data from NASA’s Huygen’s Probe.

“What’s special about that mission is that the data it took, the images it took from the surface of another planet, was beamed back to Earth and ended up on a server . . . where, official or not, I was able to access it and play with it. And I got to experience the thrill of being able to look at NASA data right after it had come down to earth, right from the surface of another world. And I very much remember the thrill of being treated as an equal . . . I never forget how powerful it can be [when] we start treating . . . people as our as our peers [and] letting the public enjoy and take part in our discoveries” said Barentsen.

Through Kepler’s Guest Observer Office, Barentsen and his colleagues worked to break down barriers between the data being collected by the telescope, and the public. They made the data freely accessible, and built community software tools that made it possible to look at and interpret that data without extensive scientific training. “We managed to turn Kepler into a mission that made all its data publicly available right away . . . on a public website where anybody could access it. Which actually led to citizen scientists, i.e. volunteers who actually know a lot about astronomy but are not professionally paid to be astronomers, they would go and grab the data and they would often find planets . . . before professionals would look at those targets, which I think is great because NASA is publicly funded,” said Barentsen.

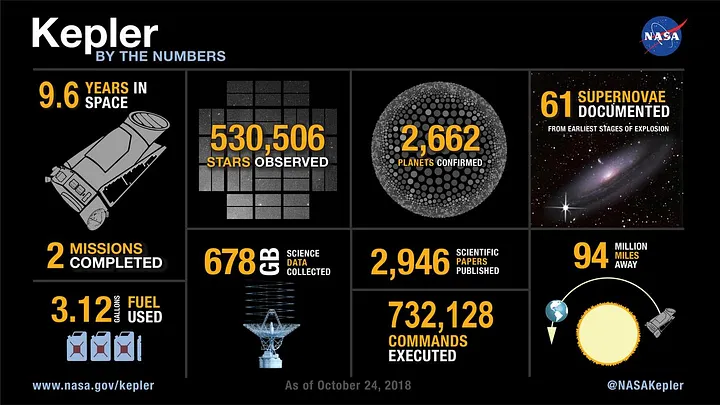

The Kepler space telescope is done with its work collecting astounding science data showing there are more planets than stars in our galaxy. Here’s a round-up of what Kepler has achieved; Image: Wendy Stenzel

It wasn’t just exciting for the members of the public to have access to this data and the tools to look at it — it also had an impact on what could be discovered in the data, and how quickly. “The Kepler Telescope observed about half a million stars . . . No single person can look through half a million stars in great detail. Of course, these days, algorithms are as important as people. . . . A single person can write an algorithm . . . but a single person is never smart enough to make sense of [the results]. So we need teams and expertise from everywhere,” said Barentsen.

One of the ways Barentsen and his team brought in broader expertise was through the building of open source software tools like lightkurve. The tools enabled anyone to go to a website, take a script, execute commands in a programming language, and discover a planet. “We’ve had incredible feedback on that,” said Barentsen. “We use a platform that’s very common now called github, where people collaborate on software, and that’s been key. Our tools would be nowhere near as good. We had a team of about four or five people at BAER, but . . . our most popular tool ended up having 40 contributors. So we have 10 times more people contributing to our software than just the size of our team alone,” said Barentsen.

Once the tools were built, Barentsen and his colleagues went out into the community to promote them, and train the public on how to use them. “One year we even did events like Comic-Con [and] South by Southwest . . . we were part of the NASA booth. . . . NASA has a lot of fans . . . people really tend to love NASA and be inspired by it. Especially young people. . . . They’re all talented people and they all love NASA, but nobody’s ever gone and said, ‘Well, hey, you with your talents, did you know that if you go here and use the data in such and such way, you could be discovering planets instead of selling ads for people to click on?’” said Barentsen.

Barentsen and his colleagues promoted their tools at a wide range of events, including conferences, meet-ups, citizen science programs, and schools (you can watch Barentsen’s colleague Christina Hedges introduce their lightkurve software at a SFPython event). All told, more than a million volunteers participated in looking at Kepler’s data — some would discover planets while still in high school. “The Lakia twins. . . . they educated themselves, I think at age 14 or 15, [on] how to use the tools we created to go and look for their own planets in the Kepler data. And they succeeded. . . . they did such a great job that they ended up going into an astrophysics program at Berkeley, the nearby university, where they are now professionally doing, I believe, Master’s graduate research using Kepler data. Once we started hearing about them, we invited them to NASA. . . . they ended up giving, as sixteen year old twins . . . a presentation to the Kepler team at NASA, which I think is brilliant. . . . And they’re one of many examples which helped us realize that the discoveries that come out of these NASA missions are more often than not limited by talent and the availability of people to look at [the data] with different eyes and different methods and different ideas than [by] the actual data . . . The telescope in space doesn’t make your discoveries — it’s always a human on earth, looking at the data. And with Kepler, we have so many examples of people who contributed meaningful science, even though they were not part of the Kepler science team,” said Barentsen.

Kepler Program VIP’s from left Jon Jenkins, Natalie Batalha, and Bill Borucki pointing at the NASA Ames Hyperwall in the NAS (NASA Advanced Supercomputing) facility filled with exo-planets discovered during Kepler Mission. Moffett Field, CA (for aviation week); Image: Eric James

The impact of Kepler’s Guest Observer Office goes beyond the Kepler mission. “Perhaps one of the coolest things to come out of this is that the new mission that followed up on Kepler, called Tess, ended up making the data available right away to everybody. And I think that’s in part because we started doing it, and adding to the notion that we’re all public servants at some level because these facilities, these telescopes, they cost a lot of money, a lot of taxpayers money. . . . I believe that now, as of last year, it is a policy of NASA science to, as much as possible, make all data from all new missions public right away, including tools and methods. So I think in 10 years from now, this is no longer going to be a discussion. It will be obvious that we should be doing this,” said Barentsen.

Barentsen hopes that this type of investment in public access to NASA mission data, and the tools for the public to look at and interpret that data, continues. “NASA is really good at building spacecraft and making sure the spacecraft work well, are safe, can be launched safely and take data at a good quality. And historically, we’ve always invested less money in helping people then use that data. If you look at the typical budget of a NASA mission, I don’t have the exact numbers, but at least 90 percent goes to building the spacecraft and only like less than a percent tends to go towards helping people understand the data once it’s in the data archive. And I think there’s an opportunity there to make more teaching resources, teaching materials, [and] tools to help people explore [this] data. And I think that can really contribute to making our field, which historically has been very white and male, to make it much more diverse, hopefully, which would also lead to more diverse discoveries and ideas. So NASA has a lot to gain there,” said Barentsen.