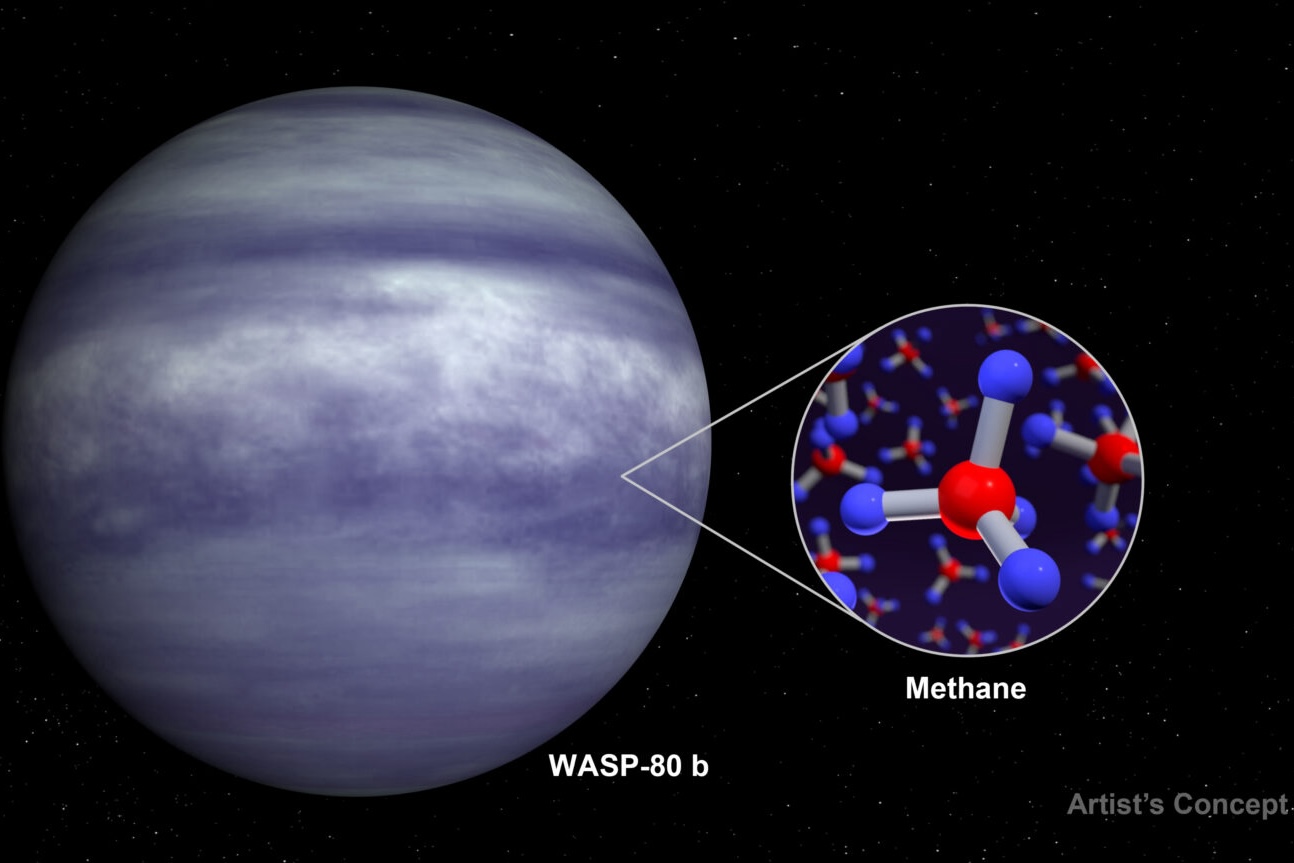

BAERI’s Taylor Bell and a team of researchers have identified the presence of methane in the atmosphere…

In Conversation, Women at BAERI: Dr. Christina Hedges

We interviewed Christina Hedges, an astronomer and scientist working on NASA’s Kepler/K2 space telescope mission. Kepler launched in 2009, and its mission was to search for planets around other stars. Losing two out of four reaction wheels on the telescope in 2013 ended Kepler’s initial “prime” science mission; the mission was rechristened to K2, its extended mission, observing for another five years until late 2018.

Dr. Hedges works mostly with python computer programming, and develop toolkits and pipelines for the reduction of datasets in the Kepler/K2 Guest Observer (GO) Office. In her previous work at University of Cambridge, she worked on a reduction toolkit for HST spatial scan mode data and machine learning. Now, she works directly with Kepler data to discover new exoplanet candidates, searches for disks around young stars, and investigates sound waves in stars, called asteroseismology, an exciting field that informs astronomers about the internal structure of a star.

Can you explain a little bit about your research and your role in the K2/GO (Guest Observer) Office?

About 80% of my time is supporting the science community. That can encompass a lot of things: such as developing software for the community, to directly using Kepler/K2 data. I’m a core developer for our in-house packages (ex: lightkurve) that different audiences can use — from professional astronomers to amateur astronomers — to easily access and work with data.

I also document and write tutorials, then deliver workshops on how to use this software. Another side is helping the community directly. For example, someone may ask about a funny signal they’ve observed over Kepler/K2 data, or perhaps an individual working on a paper needs help to detrend K2 data. I get to work with the greater community and help out.

Will this be the standard going forward? Kepler has now passed the torch to TESS [Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite]. Will it continue that anyone in the community, not just professional astronomers, can access the data?

Yes, TESS will continue this trend. Kepler/K2 has been great for citizen science. We have things like Planet Hunters, where citizens examine and identify planets in a dataset. Kepler was a pioneer in creating this type of bridge for people to access exoplanetary science. In the Guest Observer office, we are keen on ensuring all tools are accessible. Part of that means we work on improving the API, (aka the user interface), making sure it’s easy to use and remain conscious of what the consumer wants!

Is this a form of outreach, working with the science community? Or is it more about creating better products for future research analysis?

It’s more about creating a better product. There are a lot of scientists that need really easy-to-use tools, so they can focus on extracting their science. From students to professors. Python might not be their first “language” so it’s important to keep it accessible. Also, you want to leave these tools in a state that can be accessed by anyone 10 years from now.

As a young person going into astronomy, would you tell her to take classes in computer science?

Absolutely. I tell my interns that is one area to help improve your career trajectory. Take python, learn how to code, learn best practices. It’ll make it much easier for you to build your own tools, and use other people’s tools if you’re good at debugging and using API.

How did you get involved in astronomy and astrophysics? How did you decide that you wanted to do this as a career?

I had a strange moment in high school where I had two pathways to choose from: do I pursue art or do pursue physics? I loved art and painting. One of my teachers encouraged me to try for physics, as I could always continue doing art and painting as a hobby. As I was attending my physics program I decided to take physics with astronomy, I’ve always had an interest in astronomy and wanted to push myself in the astronomy field.

You and Ann Marie (Dr. Cody, also in the K2 GO office) both have, what sounds like, a creative background or at least a strong interest in the arts. From an interdisciplinary standpoint, does that help you see things a bit differently in your field?

It’s very worthwhile being creative in astronomy. Even from a standpoint of creating a visualization, how best to explain things to an audience, to creative problem solving. It can be immensely useful to think outside the box.

Have you had to overcome gender barriers over the course of your career? Can you give any advice?

Yes, be picky about your mentor! It can be so easy to fall into this trap of thinking, “oh lucky me, so-and-so wants to choose me!” rather than thinking, “hmm, do I want to study under this person?” It does come back to having a degree of confidence in yourself. But really scrutinize who you’re going to give your time, attention, and respect to – make sure you’re in a nurturing environment. Ask yourself: Is this the group I want to be in? Is this department for me? All the while taking in that confidence, care, and respect for yourself. It can be quite destructive being part of a negative environment.

How important do you feel is science communications is in your role?

Some of my work as a support scientist is science communication, but more to scientists. Creating presentations, workshops, tutorials, and YouTube explainer videos. It is in a way outreach – it is accessible for anyone – but the main audience for what I do is aimed at people who are already in astronomy, other experts. That being said, I’m always happy to do engagement and outreach, especially with members of the public. I don’t think I have as much of an opportunity to do outreach for the public currently.

Do you have mentors you look up to?

Yes, absolutely. Jessie [Dr. Dotson, Project Scientist for Kepler/K2] is one of my heroes. Jessie has so much experience and she’s an excellent leader. Scientifically I look up to her, we just wrote a proposal together! She’s methodical, caring, and professional. Also, my mentor at Cambridge; I definitely look up to him.

Interestingly when I arrived here [at the K2/Go office] I noticed we have a female project manager, a female project scientist, a female mission scientist, and Ann Marie in all these really bad ass roles that I look up and can see myself in. It’s a different experience when you see it and think, hey, I can do that! All these badass ladies. Three key leadership roles here are all taken up by women. And although that wasn’t always the case at Kepler, it’s pretty amazing now!

Who would you say was a big influence in your life, who helped guide you in this direction?

There were so many teachers along the way. In each career stage, I’ve had one or two people always pulling for me which has been great, like 1-2 teachers who encouraged me to pursue math or encouraged me to pursue graduate school. There have been a few mentors along the way. But, at the same time it’s not an easy thing to do. It required a lot of self-motivation. Pushing yourself in that direction.

I think anyone would be very lucky to be interning with you, as you’d probably push them in a good way.

I hope so. In a good way! [laughs] It all comes from caring. Pushing students to get the best effort out of them. I’m very grateful for all my mentors along the way.

What are your next steps? Any upcoming geek out moments?

I just finished resubmitting a Hubble time form. We are going to try and measure the atmosphere of a planet. This is done all the time in the field, but this is a very, very small planet. If we can find water signatures on it that’s going to be very exciting. There’s also another team that is taking different measurements in the system so we’re going to intercompare data, which is pretty new. Also, the chance to use Hubble is wicked cool!

In terms of working on things like this, is it a fairly big collaborative effort?

I’m the PI for a proposal I submitted, I’m focusing on the data analysis side. So, looking at the observation, taking the data, and calibrating it. We’ll be going from raw observations to our best estimates of the actual spectrum of the atmosphere. Then, I have other team members who will be fitting atmospheric models to that spectrum. Other team members will use another data set, again from Hubble, where we are going to be comparing them. This is all a little way down the line, but it should be pretty great!

As part of Kepler/K2 project, I’m so use to having open source data now. This has dramatically helped my development skills 10-fold. Now I’m going back and dusting off all my reduction routines and trying to package them up into a new pipeline, using some of these incredible new skills I’ve gained in statistical packages and statistical analysis since I’ve been working here.