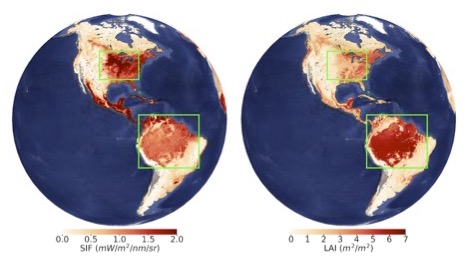

For decades, scientists have used satellite data to assess the health and greenness of Earth’s…

Sharing Earth Knowledge: The Indigenous Peoples Initiative

By Jane Berg

The first photo taken from space was captured by a rocket-borne camera launched from New Mexico in October 1946. It showed a grainy black-and-white image with clouds and a sharp horizontal line where the atmosphere ended and outer space began. As the Space Race gave us the ability to reach greater extraterrestrial vantage points, NASA’s Landsat satellites began to take photographs of Earth’s surface for research purposes, a process known as “remote sensing.”

The data are publicly available and used in a variety of ways. Most non-scientists, however, need tools and training in order to understand and utilize these data effectively. NASA’s Applied Sciences Program aims to bridge this gap and enable people to use scientific information for their own purposes.

The programs under this division are almost as diverse as Earth science itself. They range from environmental monitoring and disaster response, to health and air quality. But there’s only one that focuses on Indigenous lands and territories of the USA. The Indigenous Peoples Initiative (IPI) aims to build relationships between scientists and Indigenous communities through remote sensing trainings, community engagement, and creating diverse Earth science opportunities.

The Art of Mother Earth at Window Rock

Towering over a memorial park in the capital of the Navajo Nation is a large red sandstone formation with a circular hole that gives the city its name, Window Rock, Arizona, or Tségháhoodzání in Diné Bizaad, the Navajo language. Historically, there was a pool below the stone structure where healers would collect water for use in Tóee, the traditional Waterway Ceremony.

On April 4, 2023, the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock hosted a one-of-a-kind gathering, “Nihimá Nahasdzáán: The Art of Mother Earth Gallery Event.” The IPI partnered with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the Navajo Nation Museum, Google, AmericaView, and the World Wildlife Fund to co-create an evening filled with activities, including family-friendly games, a storytelling station, and a meal. The Navajo people refer to Earth as “Nihimá Nahasdzáán,” or Mother Earth, and that day, her portrait was the main attraction. On the walls of the octagonal gallery, people could peruse satellite images of the region: an app was developed for the event, which allowed visitors to choose a location to view from space (many people looked at their houses first), and printers were available if they wanted to take those images home with them.

IPI member Nikki Tulley, a citizen of Dinétah (Navajo Nation), is completing her PhD at the University of Arizona. She first started working with the IPI as an intern in 2020 and is now an assistant research scientist with BAERI and NASA’s Ames Research Center (ARC). Tulley works from Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she spoke to me over video call just a few days after getting back from the trip to Window Rock. She said the event took place in her old school district and drew over 100 attendees from a 45-mile area, including family and people she grew up with.

Tulley said that she can’t remember ever participating in something quite like this before, either with NASA or as a community member. “I don’t often share what I do at work,” she said. “Some people commented that it was nice to have somebody bring this type of event back to the community.”

Listening to Needs, Not Making Assumptions

The day after the Window Rock event, the IPI team held a roundtable discussion with the Navajo Nation Department of Natural Resources. The IPI program manager, BAERI’s Amber McCullum, an applied Earth scientist with ARC, explained that the discussions are essential in order to listen and learn about current activities and community needs. These dialogue sessions build trust, establish relationships, spread awareness about the program’s capacity-building efforts, and help the IPI team find out what is useful to the community in the first place. McCullum says it’s as simple as asking people what they need and then seeing where NASA Earth Observation data could support those needs: “We’re not coming in and saying, ‘here’s what we can do; we’re going to fix all your problems; check us out, we’re awesome.’”

According to Tulley, these initial discussions help the IPI and others avoid making assumptions about the best use of the technology. “[The discussions are for] the community to speak for themselves about what they’re experiencing in the landscape and to be able to share what they feel are some of the best areas where this [technology] could be helpful.”

Some of the Initiative’s most tangible activities are training workshops that introduce remote sensing technology and teach people how to use it. But these workshops are not one-sided transfers of information. Over the years, McCullum has tried to tailor the workshops to the particular interests and concerns of a community. The Initiative’s work with the Samish Indian Nation in the Pacific Northwest, for example, highlighted changes in the location and availability of a sea kelp that is important in the traditional cooking of salmon. The IPI team also conducted a training with the Sault Ste. Marie Band of Chippewa Indians, focused on topics such as land-cover mapping, including wild rice cultivation and species monitoring. NASA data have limitations, however, in terms of what they can measure. The data can’t, for instance, identify the location of a species of mushroom one tribe was interested in, which is an example McCullum often gives of where NASA technology may not fit the research or management needs.

Looking at Drought through a New Lens

In 2015, McCullum and the IPI’s founder, Dr. Cindy Schmidt, visited the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources (NN DWR) and began to discuss the possibility of using NASA data and tools to monitor drought across the vast landscape. Over half of the Nation is classified as desert, and annual precipitation may be as little as 7–11 inches, much of which is delivered by brief rainstorms in August and September.

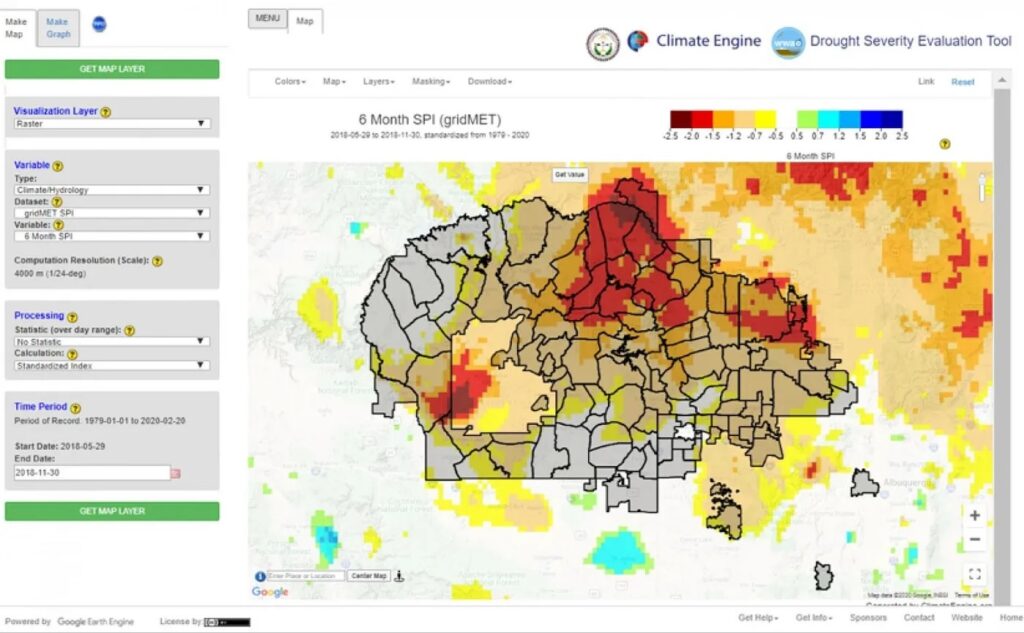

The Drought Severity Evaluation Tool (DSET) is a drought monitoring tool that was co-developed with the NN DWR and the Desert Research Institute. It began as a NASA DEVELOP project and was later funded by NASA’s Western Water Applications Office. The DSET combines various Earth Observations, such as Landsat, drought indices, and data from the Department’s network of 85 rain gauges across the Nation. “The idea was to fill in the gap where the rain gauge data didn’t have the coverage needed, in order to use remote sensing to understand drought on a finer scale,” said McCullum.

Through the continual feedback and support of Carlee McClellan, a senior hydrologist at the NN DWR, the DSET developers were able to tailor the tool to the needs of the Department, adding specifics such as administrative boundaries and summary reports. “There are various indices that people could use,” said McClellan, who spoke to BAERI in 2021, shortly after the tool was completed. “If they were interested in watershed restoration or wetlands, you could go back maybe 10, 15 years and look at a given meadow or wetland and see how that’s changed,” he said.

However, McClellan wasn’t all that optimistic that there would be wide-reaching uptake of the technology. He noted that many managers liked the tool but didn’t see where it would fit into their responsibilities and workflow. “It has a lot of capabilities, a lot of bells and whistles, and thus far, we have not used it to its full potential. So that’s just the honest truth of where we stand with things,” he said.

Two years on, McCullum agrees that one of the ongoing challenges is transitioning tools and technology into the hands of partners and sustaining that support. Continued relationship building, as with the Navajo community event that just took place at Window Rock, can help bridge those needs.

Global Observations, Global Conversations

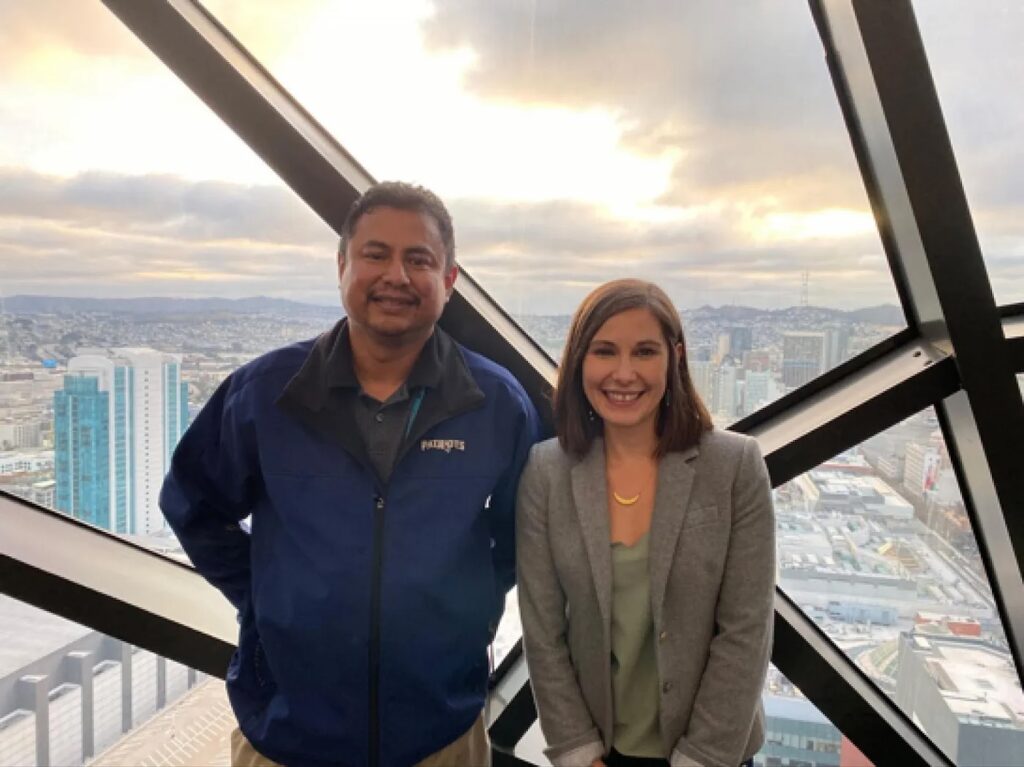

Because NASA’s Earth Observations survey the entire planet, the IPI is also engaged with and supports international efforts. During the GEO Week 2019 Ministerial Summit, James Rattling Leaf, Sr., principal at the Wolakota Lab, LLC, and member of South Dakota’s Rosebud Sioux Tribe, traveled with Cindy Schmidt to Canberra, Australia, to participate in an Indigenous Communities Side Event.

Rattling Leaf described being impressed by the gathering. “I saw that [the Indigenous people at the conference] were already doing a lot of cool things in terms of working with young people, working with drones, working with data sovereignty and data governance from an Indigenous perspective. And since we’re all different, there was a diversity of approaches in how [we’re] working with this technology to address real problems.”

It was in Canberra that Rattling Leaf had the opportunity to co-found the GEO Indigenous Alliance, whose vision is to protect and conserve Indigenous cultural heritage through Earth Observation science. The group has since been central to both the GEO Indigenous Summit and the Indigenous COVID-19 Hackathon 2020, a crowdsourcing challenge to co-design computer technology solutions for COVID-19. “So now we have a global organization starting up, and people are coming together under this alliance and trying to advance our needs with Earth Observation,” said Rattling Leaf, while mentioning that this also provides opportunities to collaborate on other issues. “We’re looking at cultural heritage protection. We’re looking at climate change, COVID-19, at intergenerational knowledge transfer, and traditional knowledge in our languages.”

Speaking more generally, Rattling Leaf said that he thinks of science as “Earth knowing” —that it is about “supporting our Earth, knowing the Earth is really our authority, in a way, [over] how we should make decisions about the Earth.”

This approach to the natural world is an area where McCullum feels that scientists can improve. “I think there are a lot of questions out there that we don’t necessarily think to ask,” she said, noting how scientists often approach nature “piece by piece” in order to find answers to specific questions. By contrast, she said that her work with the IPI has helped her think about systems in a more holistic way.

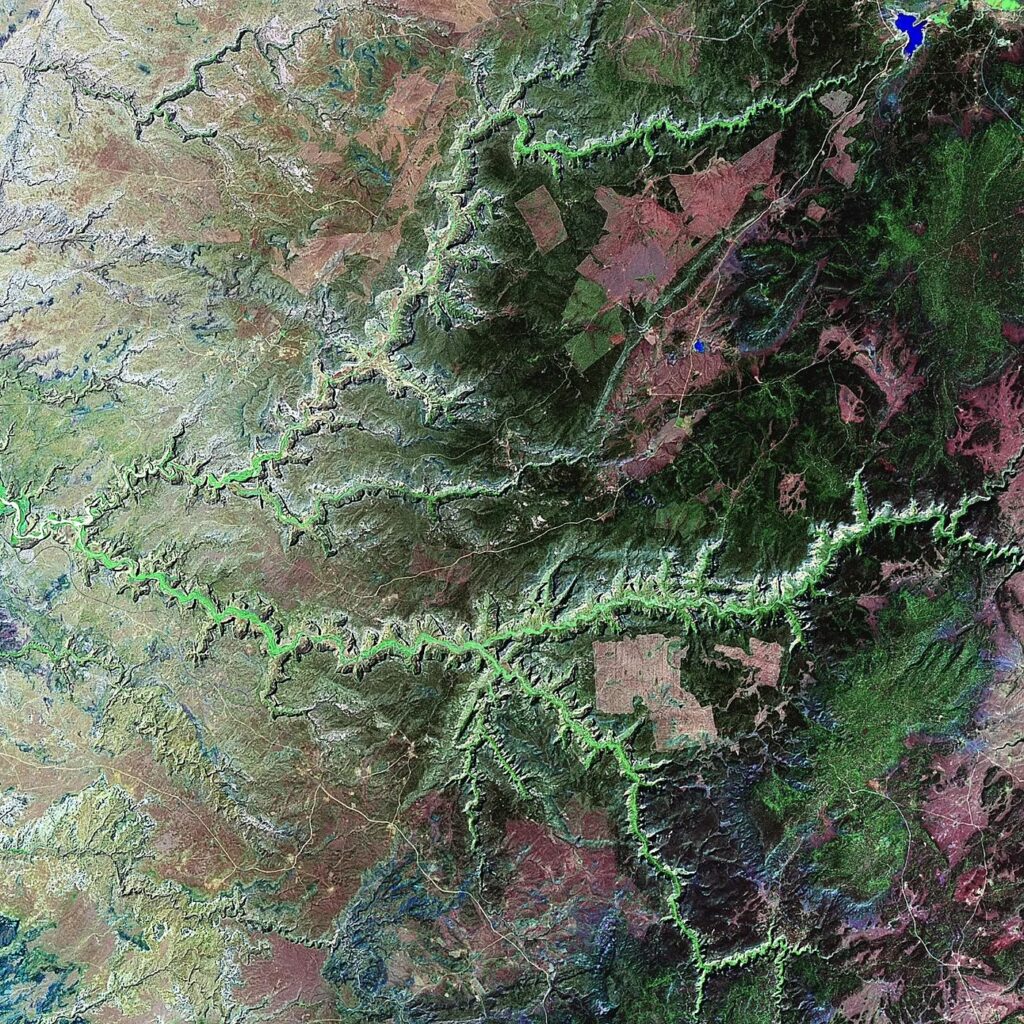

Half a century after that first photo was taken from space, remote sensing has helped us document phenomena like the volcanic eruption of Mt. St. Helens, deforestation in the Amazon rainforest, the retreat of the Alaskan glaciers, and the shrinking of the Aral Sea in Central Asia. Although perhaps not as poetic as Bill Anders’s Earthrise or as humbling as Voyager 1’s Pale Blue Dot, remote sensing images are the detailed self-portrait that we need to accurately view our changing world. And the Applied Science Program’s initiatives like the IPI are a way for more people to share and utilize these perspectives.