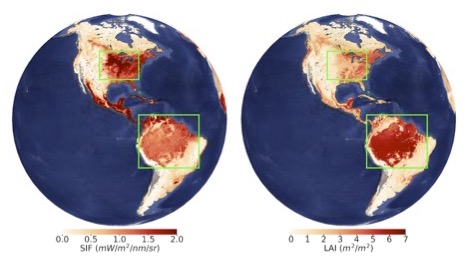

For decades, scientists have used satellite data to assess the health and greenness of Earth’s…

Kristina Pistone on what it’s like to work as a climate scientist

In this episode we hear from climate scientist Kristina Pistone about her research, her role on the sustainability commission for the city of Sunnyvale in California, and how our current system of science funding impacts her ability to do her work.

Listen here or on Apple Podcasts, Audible, Spotify, or Google Podcasts.

Pistone on a field campaign in São Tomé

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

BAERI: This is For the Love of Science, a podcast from the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute. I’m Erin Bregman. In this show, we hear directly from the institute’s scientists, engineers, and mission specialists about the groundbreaking research they’re doing right now in Earth, environmental, and space sciences, and learn about what their work can teach us about our Earth and our universe.

In this episode I speak with climate scientist Kristina Pistone about her research, her role on the sustainability commission for the city of Sunnyvale in California, and how our current system of science funding impacts her ability to do her work. Here’s Kristina.

KRISTINA PISTONE: My name is Kristina Pistone. I am a research scientist at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute. My field of research, I would say, is climate science and atmospheric science. My current research focuses on the effects of atmospheric particles on clouds, specifically like smoke particles. Smoke has sort of a dark color. It absorbs the sunlight that hits it. So it has localized heating effects and particles of any type in the atmosphere affect radiation. So it affects how much sunlight gets through, it affects how much energy is reflected back to space, and it can also mix into the clouds and change the property of the clouds. And clouds also have really important effects on the amount of heat coming in or going out in the Earth system. So understanding how these components relate to each other is something that I’m working in one small part on.

So that’s mostly what I’m doing. And then I’ve also worked in the Arctic radiative balance. So we have sea ice, which is very white and reflective, and then you have the ocean, which is a really dark surface, so it absorbs a lot of the sunlight that hits it. So since the Earth is warming, what happens? How much extra heating do we get when you replace that white reflective surface with a dark underlying surface? And can we use satellite data to say something about that? That is something that I’ve worked on but am not currently working on because I don’t have funding to do it.

Pistone in the arctic

BAERI: I actually read that paper on what happens if all of the Arctic sea ice melts and it’s quite scary.

KRISTINA: To be fair, we don’t really consider clouds, and clouds are a big question mark there. Because like I said, they can also reflect sunlight back to space.

BAERI: Yeah, and I read that I think the same day that there was an article that came out in The Post maybe five days ago that, you know, the latest results from sea ice melting in the Arctic is faster than any of the models. And it keeps happening that that’s the only direction I see — maybe that’s the only thing that is getting reported. But is that… Does that keep happening?

KRISTINA: Scientists tend to be… We tend to be very conservative in our predictions because science is a slow process and science is done by consensus. And if you’re… Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence sort of thing, so if you’re going to predict something that’s super wild and out there, you need to have really good evidence for it. So it’s easier to predict things that are sort of on the less dramatic side of things. But also we’re running an uncontrolled experiment on the only planet that we have. And so it makes sense that our predictions might be on the low end of things.

But I will note that the biggest question mark in the IPCC scenarios is like: What emissions pathway are we going to be on? It’s not necessarily in the physics of what happens in a given scenario, but the range between the potential emissions scenarios that we can do is huge. Sometimes it feels like we’re just adding decimal places when we don’t really need decimal places. And it doesn’t… It doesn’t change the ultimate take home message from what we’re doing.

BAERI: It seems pretty clear what’s going on and research in this field seems so specific. So why continue to do that specific research if we already have a clear answer of broadly what’s happening?

KRISTINA: Well, just learning something that people haven’t previously known and then hopefully communicating that and making a case for why it matters, that’s just something that’s like, why do people make art? Why do we do any of the things that we do? But yeah, at the same time, if the goal is climate action, we have enough of the science for that.

And one of the things that I think a lot of scientists and science communicators have found really frustrating is some people seem to see it as a binary between either we will get to zero emissions by 2030 or everything is doomed. But it’s really important to remember that the degrees matter. One and a half degrees is better than two degrees, but also two degrees is still better than five degrees and three degrees is better than five degrees. So even if we don’t meet these somewhat arbitrary, politically defined goals because the politicians wanted to have a nice round number of two degrees, then that doesn’t mean we should just throw up our hands and say ‘It doesn’t matter.’

We know that how much we can do matters. A lot of things, we know how to do it, we just need to sort of focus our energy on it, which can be frustrating because me over here trying to understand one small part of the climate system isn’t necessarily going towards that. But as a human on Earth, I contain multitudes. I can want to understand one part of the system better and also know that that doesn’t ultimately change what we’re saying to… What we’re advocating to politicians for what we need to do.

BAERI: And yet it does all add up. You know, it seems like one of those ideas of like every single piece seems so tiny, and yet it’s the pile of pieces together that make up the story. And so it’s that balance of like this does or doesn’t matter, but the accumulation of all of the information really does matter.

KRISTINA: Yeah. And there’s, there’s a podcast which I will shamelessly plug: How to Save a Planet. They did an episode on your personal carbon footprint. Like, does it even matter, you know, because… I mean, you can go back to recycling. It was a concerted effort by the soft drink industry and the plastic industry to be like, ‘It’s people’s fault that they’re not recycling all their plastic, not our problem because we made this plastic in the first place. So we’re going to put the onus on the individuals to do things.’ And it’s a little bit the same with the carbon footprint. But I think there’s also a balance between… There are things that we can do in our own personal lives that make a difference. But also our biggest impact is where we can come together and make systemic changes, either at the local level or hopefully at the national and international level.

BAERI: And you’ve been working towards some systemic changes on the local level.

KRISTINA: I’ve been trying.

BAERI: I’m curious what it’s like to enter into that world from the world of being a researcher and what surprises you or delights you about working towards policy change?

KRISTINA: Yeah, I mean, so I’ve been on the sustainability commission for about a year now. It’s a volunteer position that advises the city council on different sustainability issues. I think I’m still trying to find my way in it, but it’s been… It’s been interesting. Hopefully it makes a difference. A lot of it is learning how slowly things can go and how resource constrained or motivation constrained or priority constrained different things are. Because when you’re working on the very local level, the city has other priorities. And if you propose something that I think would be very cool, like how do we get rid of leaf blowers, if you want the city to actually put resources behind looking into how we would accomplish that, you have to balance it with everything else that’s going on. So it’s sort of making a case for why this is something that’s important and more important than all of the other stuff that’s going on. And I think one thing that I’d like to see more of is just how climate sustainability and adaptation to the changing climate affects pretty much everything else that we’re doing. And so rather than being its own thing, I would love to live in a world where we just, where it’s part of a larger consideration in all of the other decisions that we’re making.

So like, how do we work towards a world where the default option is not just the cheapest option because that’s usually what the decision is now, right? But how do we work towards a world where the default option is also the best one for long term sustainability? In an ideal world, we should do one thing and this is what we should do, and we should just do it. And then on the other side, there’s like: we are all operating within totally broken systems and what is feasible within these very imperfect human-governed systems? And then how do you find the balance between what we really need to do and what we know we need to do and what is actually accomplishable in these systems?

I want to be more on this side, on the first side of let’s just do whatever needs to be done. And in my optimistic days, I’m like, we frickin put people on the moon in basically a decade, right? We just decided we were going to do it and we just focused on it and we just did it. If we really focused on this, I think we could do some things. But I haven’t really seen that focus, that sort of very dedicated energy focus that we should be seeing for the magnitude of the problem.

BAERI: In your research side of things, you’re also working in a system that sounds very dependent on funding. Because you said, ‘I’m working on this thing because this is where the funding is.’ And so how does… How does the ability for you to do the work that you want to do as a scientist totally dependent on the system of funding? And are you able to do what you want to do or what would have to shift funding wise to do that? Like how does that piece of the picture play into all of this?

KRISTINA: At BAERI I’m a soft money researcher, which basically means that NASA and NSF and DOE and the other agencies have certain calls that come out every year, usually. And so they’ll say, okay, we’re looking to fund projects in the Cryosphere, or we’re looking to fund projects using satellite data from these particular satellites. They’ll have calls for particular projects that they want to fund. And as soft money people, we basically have to look at all of these calls and say, okay, I think I can write something that fits into these parameters that will do that. So it’s somewhat dependent on what calls are released in a particular year. It’s all a three year funding cycle. My biggest project now is 40% of my time for three years. And then you have to be thinking about like, well, what comes next?

And a lot of the stuff that I think we should be moving towards, like engagement with communities and relationship building with people who will actually be impacted by climate change, and I think there is some push towards that now, but these relationships take longer than three years. It’s always sort of a balance between what proposals have you written, what proposals have actually been selected, because let’s say maybe 20% of them actually get selected. Can you be on somebody else’s project where they’re leading it and you work with them? So you have to build collaborations. And then looking towards the next thing. So like what other projects do I need to be working on that will be funded? It’s not a great system.

BAERI: So you’re basically a freelancer scientist is what it sounds like. I mean, it doesn’t sound that dissimilar to a lot of arts funding and how those cycles go. There’s like very specific calls for commissions and then you kinda have to propose something that you want to do anyway, but also fits in with what they’re looking for.

KRISTINA: Yeah. And proposals are such a bummer, right? Because it’s like you put in all this effort to come up with an idea that you think is awesome and cool and like you convinced yourself that this is something that I actually want to work on. And then you spend all this time and energy writing it up and trying to make the case to other people why it’s something that’s cool and awesome and you should work on and then you send it off into the world. And then they’re like, ‘No, we don’t think it’s good,’ or, ‘We think it’s good, but the pot of money is just too small this year, so we’re not going to give you money to do it.’ And then you start all over.

The amount of money that the federal government spends on basic research is such a tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny sliver of everything that the government spends money on. And yet we are all competing for even tinier slices of that tiny slice of the pie. And this just comes down to priorities and what is allocated by Congress and how much do they want to give to NSF or NIH or NASA or NOAA or DOE, all those guys for their research money. I don’t know how we fix it other than call your members of Congress and tell them that science funding is important. You know, the policy sell for that would be ‘We have all this talent, we have all these brains, and we should use them for the public good.’ Yeah, let’s do that. I think a lot of people are pushed out who otherwise wouldn’t have been just because the funding situation is a mess.

BAERI: I find it fascinating and it’s not something that I hear talked about a lot, but I’ve become more and more interested in how it’s set up really dictates what is being done. And so I’m very curious about the setup of it.

KRISTINA: There’s so much more good science out there that could be done if only there was the money to do it. We are so cheap.

BAERI: Has the field that you’re in, does it feel like it’s changed at all since you started working in it? Either the system of it or just like the mood of working in Earth science, given the state of how things are going in the world?

KRISTINA: So I started grad school in 2008 and I was at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which is where the Keeling Curve started. The Keeling Curve is the measurements that go from 1958 to the present day, they’re still making them, showing how much carbon dioxide has risen in the atmosphere since we started making measurements. In grad school, there were always opportunities to be involved in more policy related science applications and like, how do we communicate our science outside of our own specific journals and what are the implications for the science globally? So I think my baseline was probably a little higher than people who might have come from another institution that would be more siloed or more focused just on research.

But I do think like particularly in the last, let’s say six years or so, I think there’s been more energy focused towards these sort of policy relevant science changes. I think for a lot of us, and it shouldn’t have been a revelation, but a lot of us in the 2016 election, we thought that it would be obvious enough that we shouldn’t elect someone who is blatantly anti science. And so us as scientists, for a lot of us, communicating science to policymakers or to the general public who are the voters, doing that work…Because it became very clear that science literacy and science understanding was not where it needed to be, and I think COVID has only highlighted how much more work we have to do there.

But again, it comes back to that funding question, right? I’m not funded to do that kind of stuff. I do Skype a Scientist to middle schools because I think it’s important to do and I do it in my spare time. It’s not actually what I’m being funded to do. So our systems are not set up optimally, I think, in a lot of ways, which again is no revelation to any of us. I don’t know if I answered the question there.

BAERI: Actually, I want to go back to… you mentioned the Keeling Curve, and I remember reading at one point that part of the reason that that exists is that Keeling just kept doing the research even when it wasn’t funded.

KRISTINA: Yeah, there’s a lot of that stuff going on. I mentioned three year funding cycles and this is a continuous data record that’s gone back almost as long as my parents have been alive, and it is hard to make those type of long term climate measurements given the situation that we are in with funding cycles and election cycles and all that kind of stuff, and the administration might change and then the money disappears. It’s… Addressing climate change really needs a long game perspective and we are very bad at taking long game perspectives. So everybody wants instant gratification, but sometimes you just have to do the slow, plodding work, building electrification and weatherization and putting up some solar panels, even though they’re just normal solar panels, and not… The work that needs doing is not always the flashiest and most exciting work. And it also is not something that you’re going to see immediately in the next few months or few years. It’s playing the long game and that’s really hard when every day we’re emitting more carbon dioxide and every day that we don’t do something is a little bit more, when we know what we need to do.

BAERI: Is there anything that you wish everybody understood more about climate science?

KRISTINA: All of it. It really depends on the audience. On an international level, most everybody is on board with climate action. The US is a very weird place in that one of the two major parties has decided to take the position of: ‘Well, is it really a problem? Do we really know that it’s a problem? I don’t know that it’s really a problem.’ Everybody else in the world pretty much is like: ‘No, it’s a problem and we need to do stuff about it. And now let’s have extensive discussions about what exactly we do about it and how much we do about it and who pays to do it.’ So in the US it’s kind of silly that we have to start with: Climate science is real and we know what we’re talking about.

I guess people who might dispute the scientific consensus, I would invite them to consider how much work and energy and revision goes into coming up with a document that even like ten or 15 authors all agree on. And when we’re talking about the IPCC, it’s like hundreds of authors and reviewers have written and reviewed and responded to all the revisions accordingly. The amount of consensus that needs to be present for such a document to be so unequivocal? That should tell you something. Like I said earlier, scientists tend to be a little conservative in terms of our predictions. We don’t want to predict something that’s going to be too far… That’s going to be too dramatic from what we’ve seen before. So when you look at something like the IPCC that says ‘We have to act now, it is extremely urgent,’ to have everybody on board with that message, that should tell you something very strongly about how serious and potentially underestimating it is.

Then for the Bay Area specifically, I’ve seen a little bit of a different flavor of things I wish people knew. Around here, you tend to get a lot of people who understand that climate change is a huge problem and understand that we need to urgently act on it. But you tend to get people who either think, ‘Oh, technology will save us, we can just have more electric cars, and then this problem will be solved,’ without considering all of the logistics that go into mining the lithium needed for the batteries to make electric cars be a thing. One to one replace our individual gas powered vehicles with individual electric cars? Another example of where we need a bigger picture systemic change. We can’t just replace one thing with an analogous thing. We need to think about how our systems are going to change into the future.

So you see people saying we can tech our way out of it and then you also see people talking about like albedo modification and geoengineering. And that’s a whole other flavor of we’ll just tech our way out of it. I think most of the people who are advocating for that, they’re just, they’re scared. They see what’s going on and they think there’s no other choice. I think the vast majority of the scientific community does not think that stratospheric aerosol injection is a good idea. So stratospheric aerosol injection is the idea that we would just put small particles really high into the atmosphere, it’s going to reflect sunlight back to space, cool the earth, and then “it buys us more time to solve global warming.” Those were air quotes if this becomes audio.

If you think about all the massive consensus that had to go into the IPCC to come up with the Paris Agreement and say that this is something that we need to do and these are our specific goals, the short answer is like these sort of albedo modification things are just going to be even more fraught geopolitically. And also from a science perspective, we do not understand aerosols well enough in order to be able to say that it’s definitely going to do the thing that we think it’s going to do and nothing else. And that’s going to take, like I said, science is slow, it’s going to take way more time than we have in order to actually nail down those uncertainties to something that I would feel comfortable with.

So there’s geopolitical, there’s equity issues. There’s so many issues with that. And I wish the people who are advocating for albedo modification kind of stuff would understand how complicated that would be. And in a world where we have unlimited research funding, I’d say yeah, let’s go and let’s learn more about what that might look like because science is cool and knowing stuff is cool. But it’s hard to see, again, tying back into how the science funding situation is structured, it’s hard to see how that wouldn’t just take away from energies that would be better spent towards the things that we know would work and not trying to solve problem A with potential other problem B, rather than solving A with solution A that we know we have and it’s good.

Anyway. It’s hard to say what the future will be, but… I think I have skills that are applicable to a lot of different problems in a lot of different fields. And hopefully… We’ll see. We’ll see where I end up. Maybe Congress will decide that we’re going to quadruple science funding. A girl can dream, right?

Pistone on a research flight in Namibia

BAERI: Thank you to Kristina Pistone. Our music is by Danny Clay. You can learn more about Kristina and her work at baeri.org/people/kristina-pistone. You can also find that link in our show notes. That’s it for this episode, see you next time.